Words and Interview Gabrielle de la Cruz

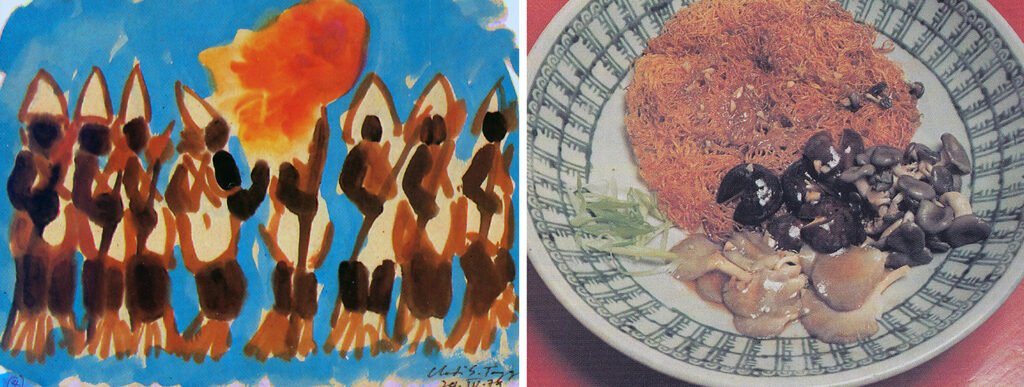

Images Claude Tayag

The Art and The Artist

“Please feel free to stop me when I am oversharing. You know how much I love to talk,” said Claude Tayag during our very first sit-down interview. The truth is that I have known him for years through Kapampangan family ties and I have listened to his stories multiple times, but it was the first time that we were having an official interview for publishing. During family gatherings, he would indulge us with stories about a newly discovered recipe, his latest wood carvings, or even just a few interesting people he met. He would get down to the smallest of details, such as what kind of peanuts should be used for a good Kare-Kare, or how long should you marinate a certain protein to get the right amount of tenderness.

When I found out that he was working on an adobo book, I immediately messaged Aunty Mary Ann, his wife, if we can do a feature in Kanto. Little did I know that this would lead to our longest conversation yet, with Tito Claude walking me through his creative journey. “I have no professional training in culinary arts. At all. Zero,” he revealed. He was an architecture student who discovered his talent for cooking by hosting little parties for his block mates and serving them good old Kapampangan food.

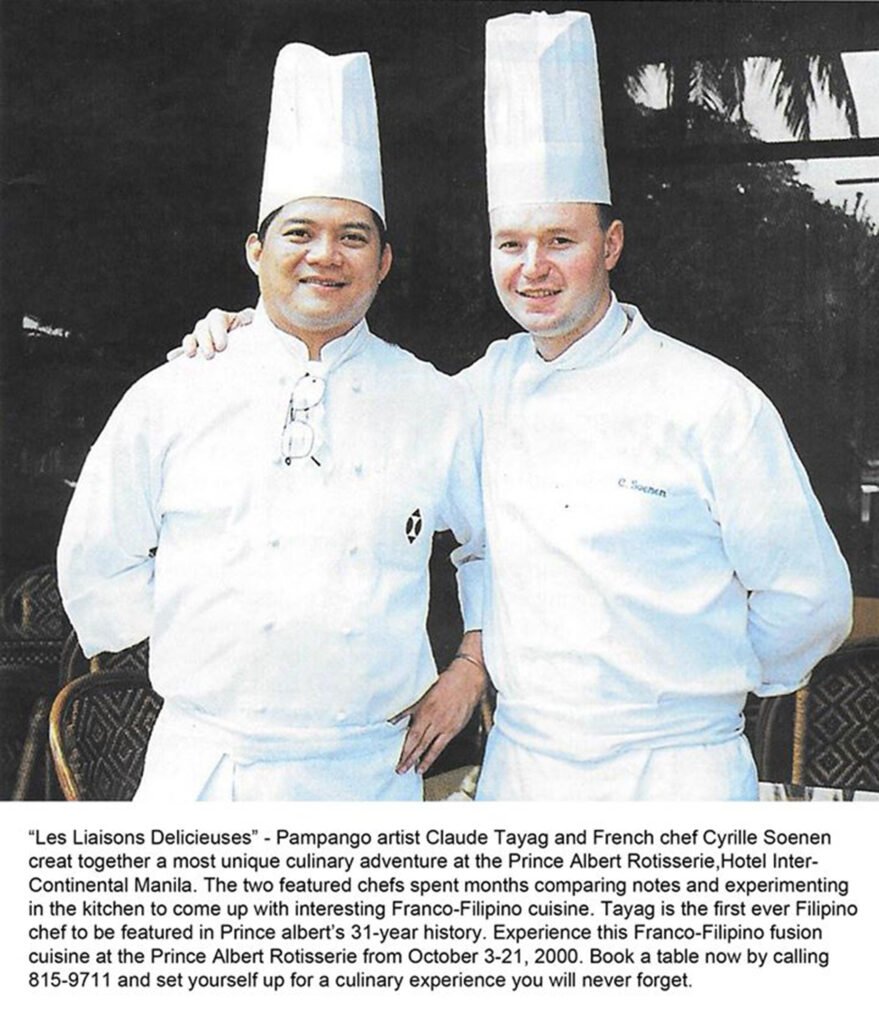

“In 1988 or 1989, at Anghang Restaurant in Amorsolo Street, Makati, I was given the opportunity to convert my paintings into edible art in ‘Art Woks’ by Claude Tayag. It happened for three weekends in a row and was the time when I was slowly introduced as ‘the artist who cooks’,” he shared. This was his turning point, realizing that cooking is one of the best ways he can showcase his creativity. This then led to more culinary event invites, a column at the Philippine Star, and the opportunity to independently redesign and convert Bale Dutung into both his house and restaurant. It was hard to stop him from his stories, as his journey is one that proves how far an artist actually goes just to keep pursuing his craft.

All About Adobo

We eventually got to the end of his story about his career journey. He then asked me what is it that I want to know about his book, with me responding that am particularly curious about how, after his years of experience in the culinary industry, did he decide to come up with an Adobo book only now. I added that I am also curious about his writing process, what lessons he learned throughout his adobo research and travels, and what the sole purpose of the book is.

Our conversation follows:

Months ago, I came across Aunty Mary Ann’s post about her “adobo diet.” She shared that you have been doing plenty of kitchen experiments as you were completing your Adobo book. Was the adobo book a pandemic project as well? When and how was this conceived?

It all started when the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) announced that they are eyeing to standardize adobo, including other prominent Filipino dishes such as sinigang, lechon, and even sisig. This happened in July 2021 and it stirred left and right conversations online.

I then decided to write an article entitled “The adobo riot: Much ado about nothing,” where I published sentiments and oppositions of people from the food industry and the clarification from DTI. This led to the Around the world in 80 Filipino adobos series, which is a documentation of my travel and research on Filipino adobo.

Eventually, all these paved the way for The Ultimate Filipino Adobo book. In a way, I have DTI to thank. If it wasn’t for that announcement, we wouldn’t be able to take the conversation further.

80 Filipino adobo dishes? That’s a lot for a series. How many adobo stories are in the book? How did you decide on which ones to include?

I honestly lost count. Help me out with that. Finish your copy and tell me how many stories are there once you’re done.

What I can tell you is that most of the stories I have shared in my series at the Philippine Star can also be found in the book, as these formed part of my travel and journey in documenting Filipino adobo here and around the world, past and present.

Let’s get into the pages of the book. What should readers expect from it? Are there any interesting adobo revelations here that have not been mentioned elsewhere?

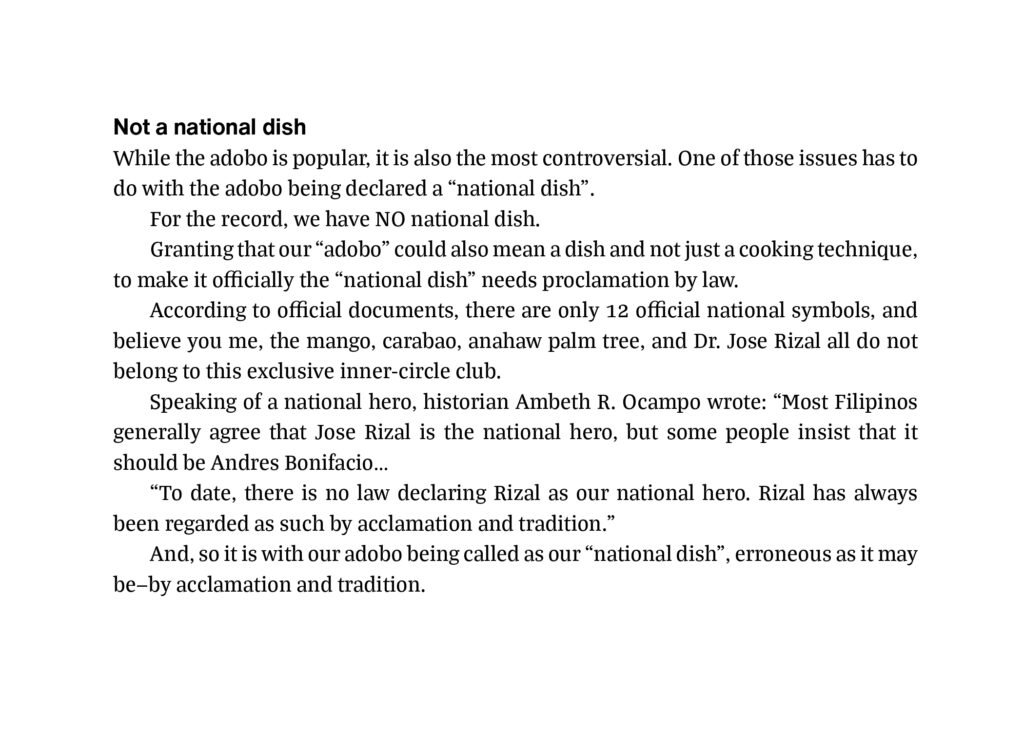

The premise of the book is to differentiate what Filipino adobo is by looking at its journey as a cooking method and a cooked dish. This is basically why the adobo book is chronological; it reveals that we were already cooking adobo prior to Spanish colonization and it opens our eyes to present adobo innovations and interpretations.

The truth is that adobo is a borrowed term and that the manner of cooking is what identifies the Filipino adobo. In its most basic definition, Filipino adobo is a cooking method with vinegar as its primary source of liquid. This is an indigenous practice here in our country, as our ancestors prepared food with vinegar and salt for preservation purposes given the tropical climate.

We had paksiw na bangus (milkfish simmered in vinegar) way before the Spaniards introduced adobo to the Philippines. We have been marinating our proteins in vinegar since the early times.

The first few chapters of the book talk about this history along with classic and prehispanic adobos, while the latter ones present different adobos by the book and by cooks. Filipinos from all over the world also shared some of their adobo stories and I included my adobo interpretations as well.

Bale Dutung, Claude Tayag’s residence and famous restaurant. Photographed by Gabrielle de la Cruz.

The book is a collection of stories, not recipes. Can you tell us more about its creative direction?

Filipino food is emotional. I wanted to showcase how cooking is tied to our culture and tradition by gathering narratives of how recipes are passed down from generation to generation or how a dish can be attached to a certain memory.

My introduction in the book reads “Adobong walang kwento, walang kwenta!” I believe that the essence of something is further understood once its story is told.

I’m glad you mentioned that food is often attached to a certain memory. I want to ask, do you remember your very first adobo meal and who made it for you?

Sorry to disappoint you, but I don’t exactly remember my first taste of adobo. I do recall my earliest memory of food. I was 4 to 5 years old. We then lived right across the big church here in Angeles City.

During Friday afternoons, our uncle, then-Mayor Eugenio Suarez would get me and my brothers Paul and Balam mainly to play with his only child. He lived in a bungalow next to his aunts’ or our grandmothers’ house, with them sharing an outdoor kitchen. When it was time to eat, our grandmother would ask us to sit on a long bench, with all of us lined up and our feet swinging and not even touching the ground.

Our grandmother would feed us one by one with a little of the paksing bangus (milkfish in sour soup), a little of sinangag (Filipino fried rice), and a piece of pitichan (Kapampangan bite-sized chicharon/pork rinds) dipped in soy sauce. This memory is very vivid up to this day because it was a crucial time for me to learn how to chew well and appreciate flavors. It taught me how to patiently wait for my turn, with the last bite of the bangus belly making it all worth it.

This is what I meant when we said that Filipino food is emotional. A bite of any dish is meant to incite a feeling. In fact, one of the people I featured in the book said that “adobo is not a recipe, it’s a feeling, it’s a moment in time.” The story I just narrated will always be one of the moments that are personally worth remembering.

You cited a line from one of the stories in the adobo book. Were there any particular ones that personally struck you? What have you personally learned from gathering all these narratives?

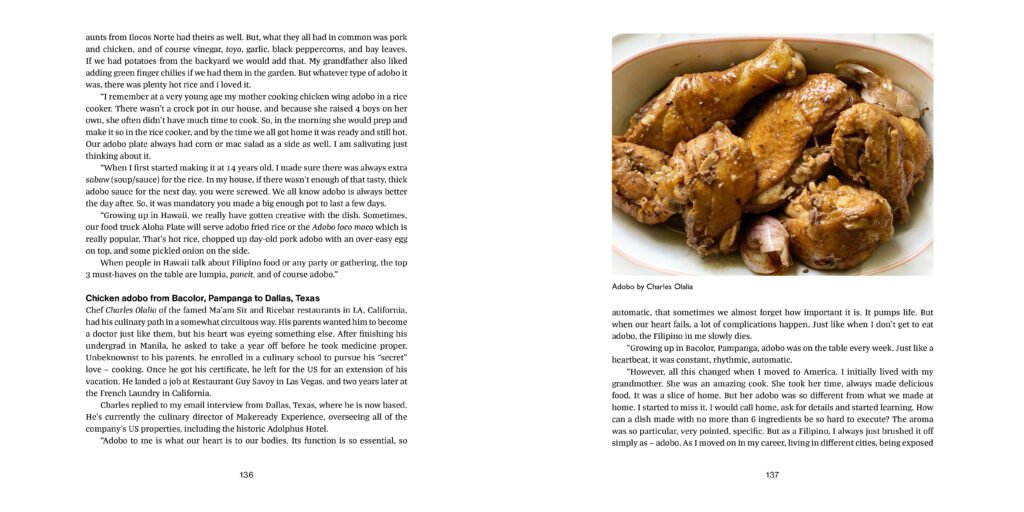

All of the stories have their own flare. Some are humorous, some are all about sticking to their culinary roots. The line I cited is by chef Charles Olalia of the famed Ma’am Sir and Ricebar restaurants in Los Angeles, California. He is from Bacolor, Pampanga and his parents initially wanted him to be a doctor. Basically, he pursued his passion by secretly enrolling in a culinary school and independently landing a job at the legendary French Laundry, a fine-dining restaurant in Napa Valley by Thoma Keller. During our email exchange, I told him that he truly is a Kapampangan, as his adobo recipe includes chicken liver.

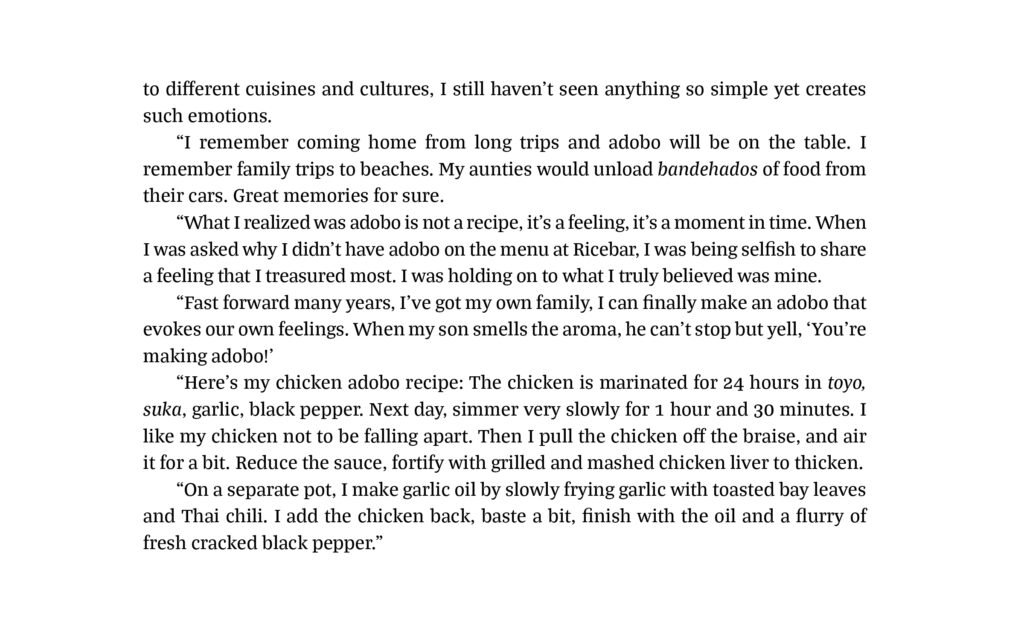

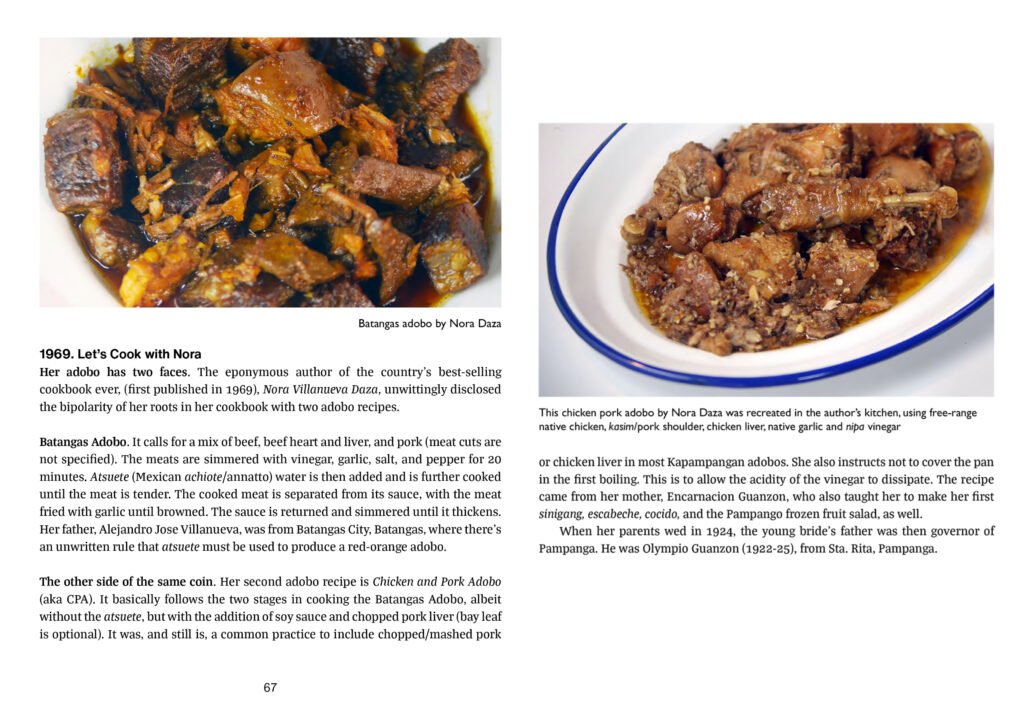

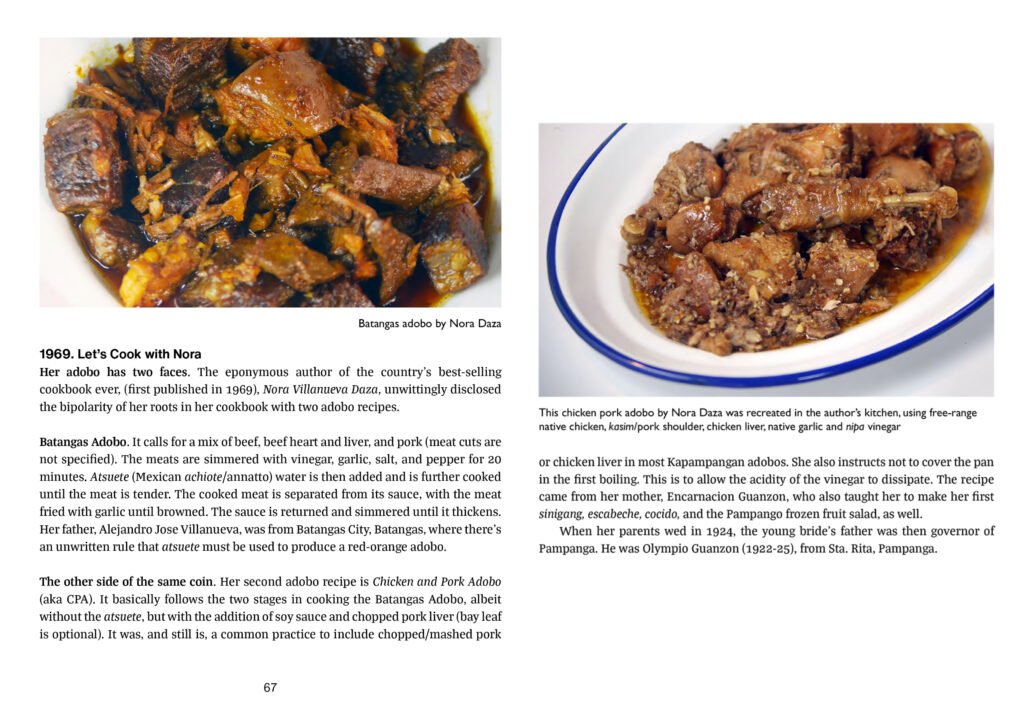

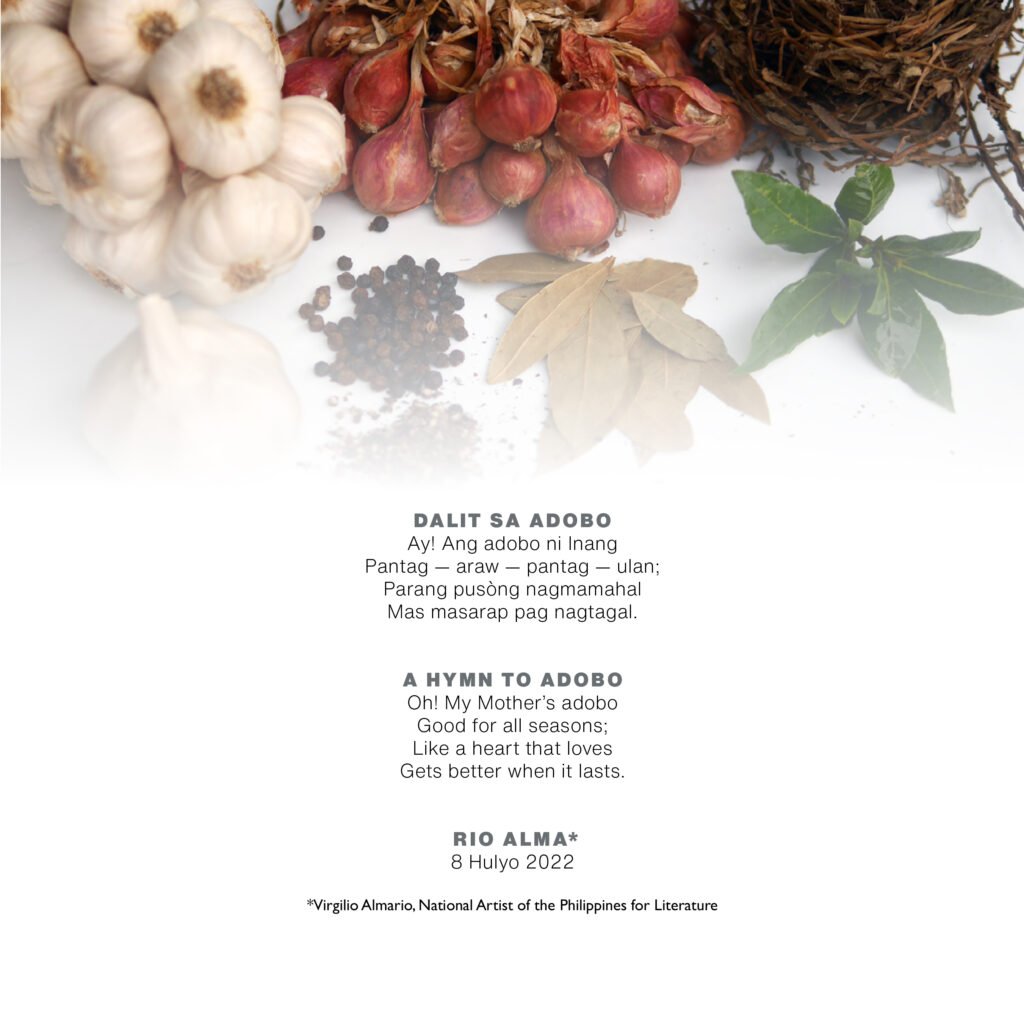

Just to reiterate, the Kapampangan version of adobo includes mashed liver. The 1969 Let’s Cook with Nora book by author Nora Villanueva Daza talked about this, along with the Batangas adobo that makes use of atsuete or annatto oil. This book is a great read as it “unwittingly disclosed the bipolarity” of Daza’s roots, as her father comes from Batangas and her mother was a Kapampangan, a Guanzon from Sta. Rita.

There are countless versions of adobo in the Philippines alone, so one can only imagine how many adobos are there around the world. Some dishes use pineapple or mango for sweetness, the good-old adobong puti which does not incorporate soy sauce, and many more.

Having various exchanges with people and reading all about adobo reassured me of the capacity of food to encourage conversations and allow people to freely express themselves. It may have been a long journey but I am glad that I was able to actually finish writing everything.

Now that you’ve mentioned writing, I recall reading a Facebook post by Aunty Mary Ann where she said that she cannot talk to you whenever you write. Can you let us in on your writing process? What would you say is the recipe for writing well?

I usually write anytime past 9:00 in the evening, as the silence helps me clear my thoughts. This just works for me.

Writing is also an art. I would go in and out of the room just to regain concentration. Most of the time, I also stretch myself across creative tasks just to be productive. One minute I could be painting, the next I could come up with a sentence that I actually want to type in. It all happens in phases.

You’re also recognized as a talented artist. Are you usually particular with your books’ visuals too? How did you design and lay out the pages of your adobo book?

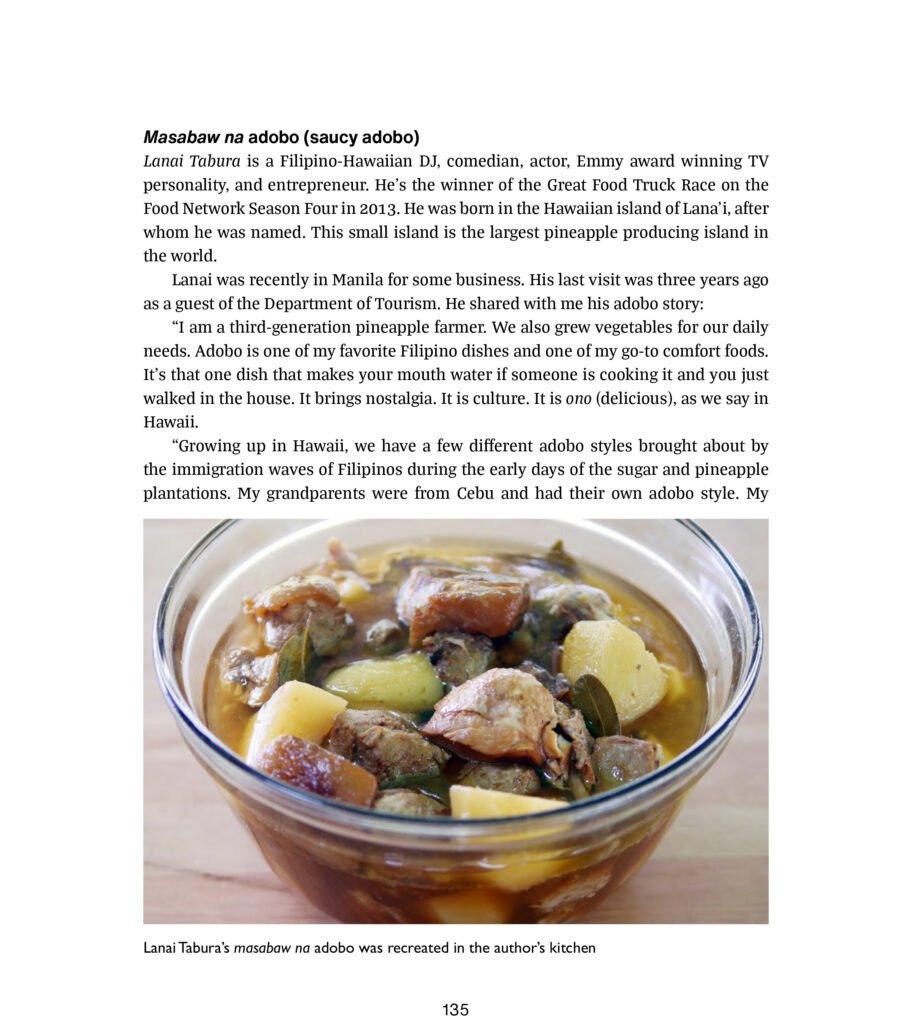

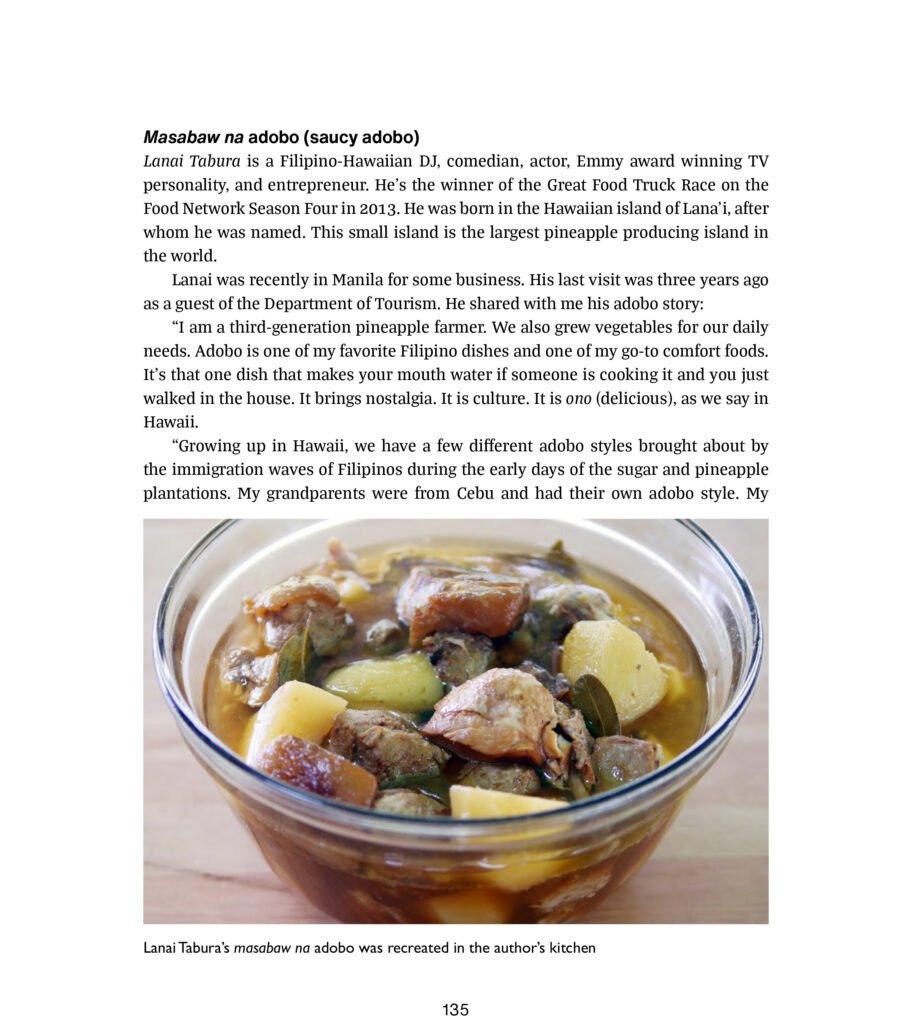

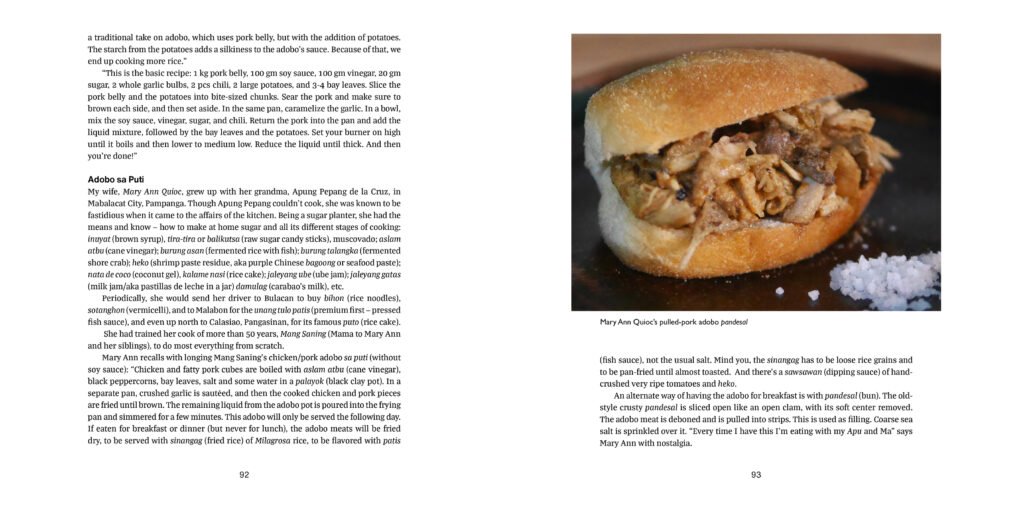

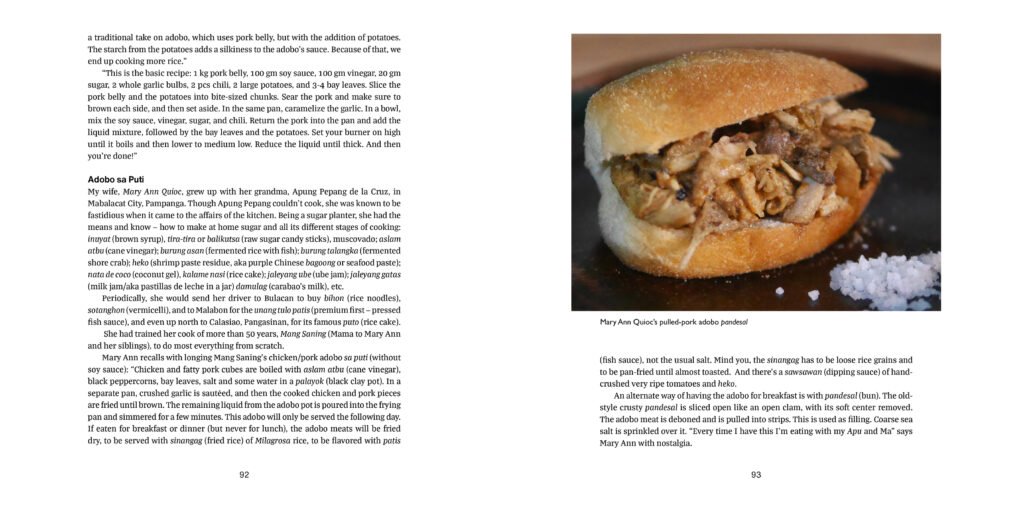

All the earlier adobo stories came with no pictures, so I had to recreate all the recipes myself. The artist in me would automatically take a snap right after cooking and plating.

The entire book took two years in the making, with the back-and-forth editing taking a total of 6 months.

I have Ige Ramos to thank for the book’s design and overall layout. He was also the one who helped me with the Linamnam book.

Now that copies of your book have and continue to reach the hands of many people, how do you want this adobo book to contribute to the discussion of Filipino food? What do you wish to reveal to the public through this project?

Somewhere in the book, I mentioned that there is never a single right way to do adobo. Come to think of it, for Filipinos, the best way to cook adobo is to cook it the way your mother does. And this is why we can serve varieties of adobos—because this method of cooking has grown and developed throughout generations.

As time goes by, eat with an open mouth and an open mind. Be open to trying a new version of adobo, sinigang, or any other dish. Push the conversation further. There are so many good flavors in the world and they all come with wonderful stories. •

Gabrielle de la Cruz started writing about architecture and design in 2019. She previously wrote for BluPrint magazine and was trained under the leadership of then editor-in-chief Judith Torres and previous creative director Patrick Kasingsing. Read more of her work here and follow her on Instagram @gabbie.delacruz.

facebook.com/claudetayag