Words Patrick Kasingsing

Images Courtesy of Gabriel Schmid (Intsia House)

A home in a garden

Swiss-Filipino architectural designer Gabriel Schmid would appreciate it if you did not label his first local project, a 1,000-sqm, two-story home in Makati, as a ‘modern bahay-na-bato-at-kahoy.’

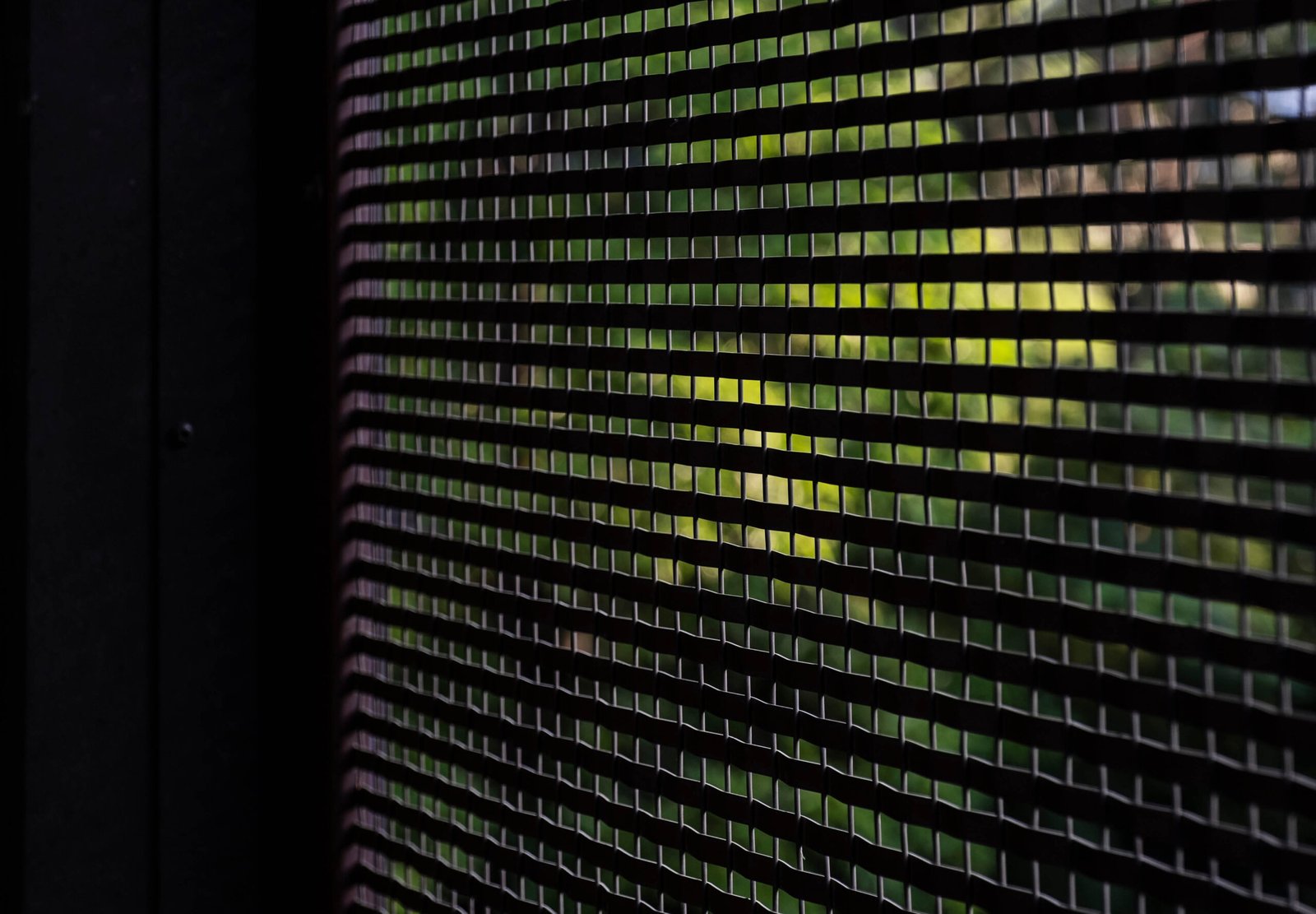

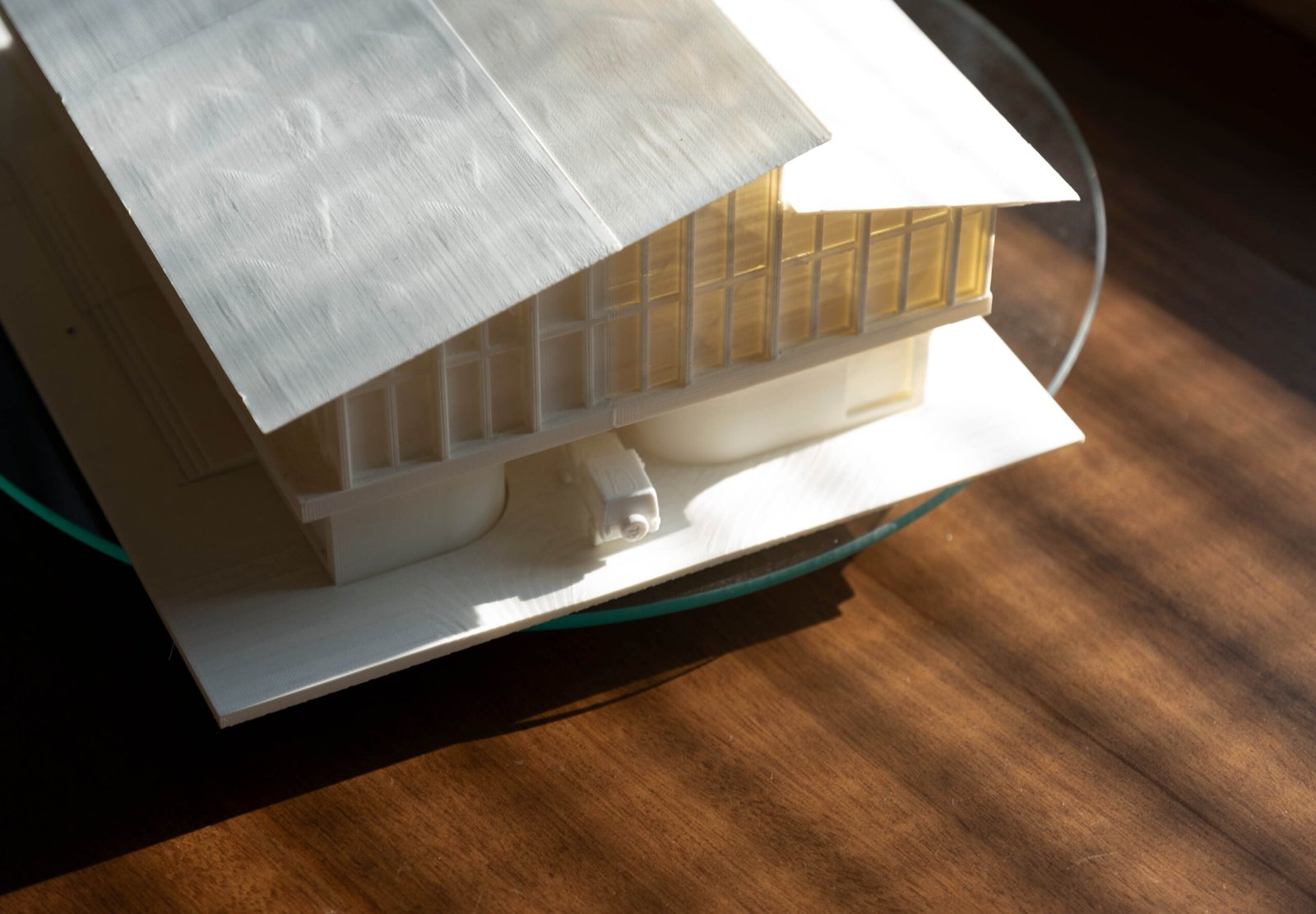

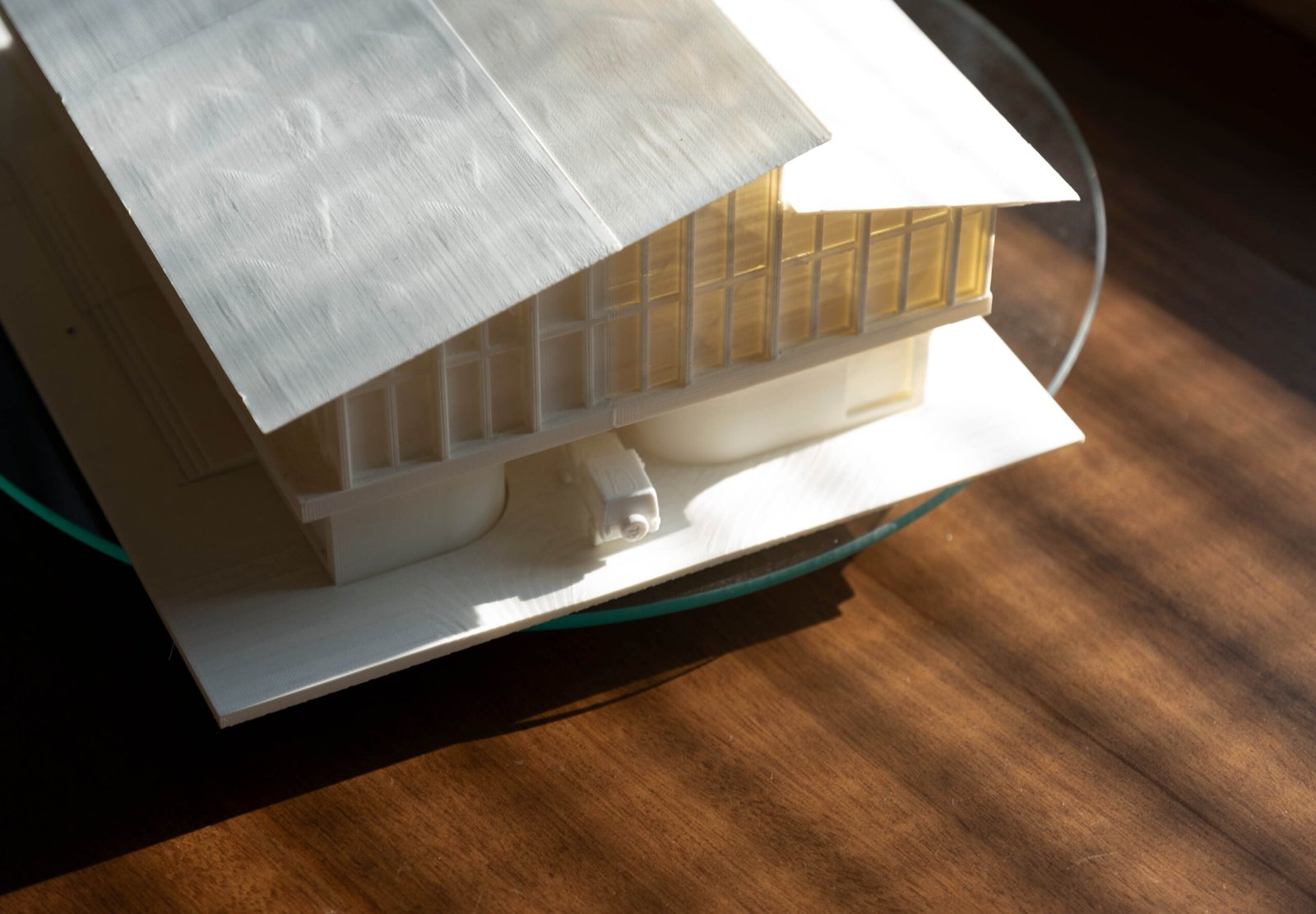

Tempting as it may be, Intsia House defies simple categorization. The home possesses a heavy, brick-clad base whose tectonic rigidity is softened by gentle, flared corners, with a procession of arches carved into the sides for windows. The second floor is in utter contrast to its dense, sculptural base, a 5-meter tall, orthogonal mass topped with a split roof, its street-facing side veiled with an expansive array of hand-woven copper screens done by the local craftsmen of Finesteel, which softens the house’s monumental silhouette and filters excess light from entering indoor spaces.

Schmid is particularly proud of the bricks and copper screens he designed: “The brickwork carries a subtle gradient; we infused the exterior bricks with some lahar to ensure it isn’t overly bright.” He explains, “The interior brickwork has a brighter mix since it will be shrouded in shadow.” Pointing to the woven screens above held together with rust-colored copper frames, the thirty-year-old designer elaborates on another one of his innovations for the home: “We used copper for the sunscreens as I was really after the patina it develops over time, where it will shed all that red color for greens.”

Many iterations were explored for the screen pattern to obtain a balance of transparency and privacy. “We eventually went with a simple overlapping pattern in two variations; the top and bottom rows of screens have a tighter weave while the row at eye level has a looser weave, one millimeter further apart, aiding in transparency but not enough to allow peeking indoors.”

The garden-facing façade is most evocative of the bahay-na-bato-at-kahoy. The flared brick base hosts a succession of arches that reveal an open lanai and an enclosed entertainment room. On top, the second-floor volume sheds the front façade’s diaphanous veil for a friendlier face; floor-to-ceiling sliding windows line the length of the home, opening onto a 1.2-meter by 28-meter balcony overlooking the garden. In contrast to its brawny pedestal, the second floor’s massive roof appears to be held aloft by spindly black steel pillars.

From the street, the house is a refreshing change from the glut of vanilla Asian and pseudo-Mediterranean abodes within the upscale village. It stands out not just for its distinctive look but also for the expansive green space surrounding it, bursting with lush tableaus of tropical plant life landscaped by designer-artist Ponce Veridiano.

The 2400-sqm lot, funnel-shaped and narrowing at the house’s unassuming gate, seems to subtly draw you in, sparking curiosity that evolves into a desire to partake in the cool, verdant space—a rarity in a part of the city home to some of the country’s most expensive lots.

“I wanted to create a home within a garden and not the other way around,” Schmid explains. “Because of the location’s land values, homeowners here often overbuild and tack on gardens as an afterthought. Ponce understood the assignment and gave us these lush pockets of green that appear naturally grown rather than curated.”

“I wanted to create a home within a garden and not the other way around…Ponce [Veridiano] understood the assignment and gave us these lush pockets of green that appear naturally grown rather than curated.”

G A B R I E L S C H M I D

A homecoming

Intsia House was conceived as a retirement home for Schmid’s parents and a Manila base for their itinerant household. This wasn’t their first home in the village; the family once lived a few streets down in a much larger house, which they sold when the couple’s three adult children moved out. After moving into a high-rise condominium, Schmid’s father grew restless and craved the gardens of his previous home and the sense of being ‘outside’ the city that their old village provided. Thus, a homecoming of sorts transpired, but on a different lot. Time away from a landed home helped the elder Schmids focus on their priorities: an expansive garden with low-maintenance plants and finishes for Mr. Schmid and, for Mrs. Schmid, larger spaces for entertaining friends and family.

After clearing the lot of its dilapidated bungalow, the family set out to build a new home; this time, its designer would be one of their own. Fresh off a two-year stint at Adjaye Architects, Schmid took on the task with gusto, splitting his time between designing his parents’ new house in the Philippines and pursuing a master’s degree at Harvard GSD. The house took five years to complete from drawing to construction, with the family having lived in their home for less than a year at the time of Kanto’s visit.

Swiss precision, Filipino intuition

More than colonial Spanish architecture, the initial source of inspiration for Intsia House’s sculptural brick base was late 60s brutalism.

Schmid laughs, “I cried a bit about this, to be honest. You do a lot of silly things when you are young. I guess it was the Swiss side of me bubbling to the surface, wanting to explore the possibilities of using cast-in-place concrete.”

With his parents giving him carte blanche for the design, Gabriel had it all worked out: he wanted a solid, sculptural concrete base for the house, featuring an arched tunnel and a screen-veiled, split-roofed volume on top.

The house hewed close to the original vision in form. However, in terms of materials, it evolved differently, and admittedly for the better, as the change arguably gave the house more character.

“The cast-in-place concrete concept failed; the sample corner we did was a disaster, and the logistics of getting 17 trucks to pour concrete in a day within an exclusive village were a headache I didn’t want to burden my parents with,” Schmid recalls. “That was six months of experimentation down the drain. I then realized that instead of complaining about construction limitations in the Philippines, we should find a solution that works with the existing system and aligns with my vision. That’s when we thought to use bricks!”

I caress one of the nearby bricks and marvel at the precision of its placement and how the roughness of each block still gave the house the highly textural base its architect desired. “All this brickwork was completed by a team of two! We devised a system that proved simple, easy to follow, and execute.”

Although the build was adjusted to match prevailing construction skill sets, precision and fine finish were sacrosanct. Schmid noted that parts of the home had to be redone because his father disapproved of the workmanship. The multiple arches and chamfered corners were executed to near perfection, a rarity. While the head of the household supported Gabriel’s explorations of aging, patina, and low-maintenance finishes, he was wary about how the materials would wear over time.

“I remember the discussion we had about the J.VAZ.CO. concrete floors. My dad asked, ‘What if it cracks?’ and I replied, ‘Then it will still look like concrete!'”

“My father, who was really my principal client, fired me twice during the build,” Schmid chuckles, “But we have a house!”

“Although the build was adjusted to match prevailing construction skill sets, precision and fine finish were sacrosanct.”

I told Schmid I’d encountered my share of compelling designs let down by poor construction and finishes, and had come to expect this as a given, which makes Intsia House a surprise.

“What I learned from this whole exercise of building our house is that no amount of schooling is going to get you the design you want if everyone isn’t on your side or if you aren’t willing to question why things are done a certain way,” Schmid shares as we finish examining the exteriors. “You and your collaborators must be on the same wavelength, so constant communication is critical. I talk to the construction workers, the foreman, the electricians—everyone, so the goals are clear. I naturally also hear them out. Take them seriously, and they take you seriously!”

When asked whether he got most of what he wanted from his vision of the house, Schmid laughed and said the vision evolved along the way. “The final version of the house becomes the vision. Of course, there may be things that we could have done differently or better, but ultimately, what comes out of construction is something I designed.”

Maaliwalas

The interior layout of Intsia House’s two floors is straightforward; all publicly accessible spaces take center stage, with private spaces on the sides. The ground floor is small and nearly cave-like in its darkness, relying on natural light from the exterior windows that open to the entry tunnel, which cleaves the house base in two. Dappled light from a tall, narrow window above the stair landing further illuminates the space, amplified by the white stucco walls. The path to the helper’s room is on the left of the main staircase, with two bedrooms situated to its right. Echoing the curvaceous exterior corners, white indoor walls billow around each room.

The main staircase is a study in contrasts: heavy yet light, cool yet warm, hard-edged yet sensual in its geometry. It begins as a cascade of concrete steps that host a selection of pottery and home décor. A slender wood railing slithers noiselessly along the wall. The staircase then turns ninety degrees, shedding its hefty concrete form for a lithe, classical silhouette finished in wood with solihiya panels between the balusters. At the top, beyond a sturdy set of wood-screened doors, darkness gives way to light.

Visitors emerge into a double-height, gallery-like space where the living, dining, and show kitchen sections merge. An unbroken array of sliding windows bathes the room in light. A narrow mezzanine projects above the entrance, hosting a long, well-stocked bookshelf accessible via a fold-in wooden ladder.

A row of automated clerestory windows lines the top of the shelves, which were open during my visit to let out the hot air. The furniture pieces balance traditional Filipino silhouettes with contemporary lines. Wood, such as narra and tanguile, is the prevailing material, enveloping the floors, walls, and ceilings in various stains and colors.

It is a curious space in that at first, one is overwhelmed by the horror vacui emblematic of traditional Filipino homes. However, as one’s eyes adjust to the abundance, you sense an invisible hand keeping everything in order. The furniture staging feels archipelagic, with each ‘island’ of objects serving a specific function. One piece caught my eye: a striking light fixture consisting of an assemblage of capiz shell discs and globes hovering above the 12-seat dining table. The fixture was a collaboration between Gabriel’s sister Rhea, who also studied architecture, and Cavite-based furniture manufacturer Senseware PH.

While the space at large mirrors its angular shell, the chamfers, and rounded corners that identify the exteriors make themselves known through the wall corners, wood joinery, and the two cylindrical volumes at opposite ends of the space. The more colossal of the two is a nearly 5-meter-tall freestanding powder room, finished in brushed aluminum and lined with a procession of tapering glued-laminated bamboo strips to break up its mass. An open cylinder formed by bamboo laminated wood slats encircles a spiral staircase near the kitchen, leading down to the service area beside the lanai on the ground floor. The two curved elements subtly break up the monumental rectilinearity of the space.

“The bedrooms were all designed to be modest in size, generally around 25 sqm, including ensuite bathrooms; I did give my parents a much larger bathroom and walk-in closet,” Schmid explains as we make the rounds of the private spaces. He points to a beautifully formed dome in the latter. “I wanted a skylight to top that, but it was not to be.”

Reflections on identity

After the walkthrough, Gabriel and I found ourselves in conversation about cultural identities. We were seated on the ground-floor lanai, facing the pool and its wall of greens, as the warm Manila afternoon made its presence felt.

I told him his indoor spaces, particularly the open-plan space on the second floor, felt very Filipino in sensibility rather than aesthetic. They captured that elusive quality of Filipino vernacular spaces, maaliwalas, without resorting to tired tropes and heavy-handed trimmings.

“I guess being somewhat inside and outside the proverbial Filipino door helps,” he offered. “I’ve had the benefit of living in the country most of my life and the privilege of an education abroad that has opened my eyes to many things.”

“Locals can overlook aspects of design or cultural identity because they take them for granted and are too immersed to view them objectively,” I replied.

“Yes, I guess you could say that,” Schmid responds. “My education revealed that while the aesthetic side of things brings delight, it is the overall experience that truly matters in the end. That means you have to ‘design’ the bits and pieces of the space you don’t necessarily see but can feel. So, this house—its being Filipino—doesn’t rest on being a stylistic homage to vernacular architecture but is an outright response to its Philippine context: the landscape, climate, sensibilities, activities, etc. That is why it’s not just a modern bahay-na-bato-at-kahoy. I believe what I have truly arrived at is a Filipino home.”

“So, this house—its being Filipino—doesn’t rest on being a stylistic homage to vernacular architecture but is an outright response to its Philippine context: the landscape, climate, sensibilities, activities, etc. That is why it’s not just a modern bahay-na-bato-at-kahoy. I believe what I have truly arrived at is a Filipino home.”

G A B R I E L S C H M I D

Like the bayanihan of yore, where the community would literally help carry the homes of others during a move, Intsia House required a talented and dedicated cast to make the jump from vision to reality. Schmid mentioned a few names. “There are the folks of Finesteel, headed by Robert Yee, who helped make my experimental copper screens a reality. Jun and Tess of Himart Jast Builders were my general contractors for this crazy build. There’s Geo Ravago, who was instrumental with the drawings for this space, and finally, dear old Ed Ledesma and his team for the construction plans!”

Schmid explains that he first met the well-respected architect when he interned at Leandro V. Locsin Partners, where Ledesma is a managing partner. Ledesma also runs a personal practice outside the storied firm.

“Initially, I had no idea how to terminate the corners of my roofs until I asked Ed for advice. So yeah, the sharp roof points are Ledesma-inspired,” Schmid says.

A home that ages

Intsia House and its creator are not afraid of change.

“More buildings should be designed to age,” Schmid muses. “It is only through age that character and soul emerge.” I agreed. It was an apt quality for a retirement home. The only challenge is getting a house to age gracefully without becoming a concern for its elderly inhabitants.

“I didn’t want the place to look new forever. I want the dirt; I want the grit. I want the brickwork to take on moss, darken, and age. The copper screens were also meant to age. I look forward to seeing the screens transition from red to green, though that would probably be in twenty or so years, and the house could have new owners by then.” Schmid is aware that tastes change. “The future owners of this home could remove the screens altogether and replace them, as the screens are hung on the façade and not permanently fixed.”

Now, how have his folks reacted to the home after months of occupancy?

“My parents are amazed; I think they really love it,” Schmid shares. “They have settled in as if they’ve always lived here, enjoying every corner! It’s truly a rewarding feeling. My dad enjoys having countless places to sit and simply savor the passage of time.”

When asked about his favorite part or moment within his creation, Schmid pauses. “I would say that… my favorite part is that it’s not really about the architecture. It’s the spaces’ capacity to harbor moments. The design does not impose itself or ‘design’ activities for the inhabitants; you can just be yourself!” •

Project Elevations and Plans

Project Team and Suppliers

Construction Plans:

Edgardo L. Ledesma, Jr., Architects

Interior Design:

Varona Architects

Lighting Consultant:

Lightspace Architects

Project Management:

Mark Lumbay Project Management

General Contractor:

HIMART JAST Builders, Inc.

Roofing:

New Kawara, Inc., TCI, Inc.

Glass Supply

NEW SJW

Concrete Works:

J.VAZ.CO, Inc.

Windows:

Kenneth & Mock Designs, Inc.

Woodworks:

ADELAC, RV Gatapia, Diamond Concept Inc., JB Woodcraft Inc., Josol Home Decor Improvement Center, Inc., Globalhome

Fiber Cement Ceiling:

Conwood

Bamboo and Installation:

Zhu Bamboo/Siy Bros. Company Inc., Strongbond Products Philippines, Inc.

Tiles Supply:

Tile Gallery, Metrotile, Mozzaico, Machuca Baldozas, Inc., Wilcon Depot, Globalhome, Euroasia

Stone Installation:

Zalverks Stone Installation

Pool Tile Supply:

Kaufman Inc., South Pacific

Backyard Bricks:

Stoneland Enterprises

Fans:

Philippine Geogreen Inc.

Tanks and Pumps:

Pumpkart Machineries Services, Inc.

Water Heating:

AVESCO Marketing Corporation

Toilet and Bath:

Kuysen Enterprises

Technical Lights:

Green Group, Inc.

Garden Lights:

Sparkslight

Door Mechanisms and Related:

SUPERFAB, Doreen V. Remegio/CAR&D Marketing, Hafele

Furniture:

OMO Furniture and Accessories Store

Appliances:

Abenson

Louvered Doors:

Giogel

Trench Drains:

CV Vega

Solar Panels:

Go Gridless

Home Elevator:

IEEI

Airconditioning:

ACCUCOOL

Generator:

MONARK

Telecommunications and Internet:

ACETECH

Speakers:

Modularity Electronics, Inc.

Motors and Servicing:

ACCESO

Kitchen Supplies and Additional Handles:

OZZIWORLD/Nine Dragons Enterprises Inc., Focus Global, Inc.

Cabinetry:

PAKO PH/Golden Fortune Prime Source, Inc.

Curtain Blinds:

Focus Global, Inc.

Swimming Pool and Heating:

Aqua Pools, Tempex Trading, Inc.

Waterproofing:

Linda Margarita P. Quibilan

Landscaping and Plant Supply:

PONCE/Proceso C. Veridiano

Gardenworks:

Marlyn N. Tortor

Gas Piping System:

GASTEK, Inc.

Pest Management:

Antonio A. Sarmiento/TSJ Antipolo Pest Management Services

Sensors, Switches, and Outlets:

BTICINO