Interview Patrick Kasingsing

Project Text Sudarshan Khadka and Alexander Furunes

Images Alexander Furunes and PAVB-NCCA

Hello Sudar and Alex! Finish any books lately?

Khadka: The Epic of Gilgamesh, Building Simply, and Stories and Reflections by Axel Vervoordt, all equally inspiring but in very diverse ways.

Let’s start! We’ll be talking a lot about built heritage and spatial inheritance, as this is our heirloom issue. What is your definition of built heritage, for starters?

Built heritage is made up of the built elements that mirror ourselves and are a beacon that illuminates our past, present, and future. They are a record of the values, memories, and identities that endure, and they connect us to our humanity across space and time.

Architecture, with its perceived longevity, naturally lends itself well to being something one inherits and uses. However, attitudes towards heritage architecture worldwide, particularly towards post-war modernism, have not been incredibly inspiring. Why do you think there is a lot of uncertainty and unease with the public (non-architect) response to heritage architecture?

Resonance takes time; architecture is a slow art that takes years to design and build and decades to understand and love.

What are some ways the government and private sector can help bridge the divide between awareness and action?

Awareness begins when both sectors invest in the quality of the buildings they produce, both in the design and the construction side. The action naturally follows. To invest in quality requires a broader discussion about what we value as a society and how we want to represent it through what we build.

Lung Tam Textile Cooperative, Vietnam, 2017

Lùng Tám is a small village located in Vietnam’s northernmost province of Ha Giang. During the Vietnam War, the village was relocated from its original perch on the hilltops to the bottom of the valley, exposing them to high risks of flash floods. The architects were invited to support the textile cooperative to expand their workplace in response to growing demand. The community organized themselves into a core group of 12 leaders who each communicated with ten cooperative members. A series of workshops were organized to facilitate the planning and design process, and ‘the grid’ was identified by the group as the guiding concept derived from traditional vernacular timber structures in the region. The concept enabled the cooperative members to map existing facilities, and together with the architects, develop a new design for the site. The design makes use of the disassembled houses still stored after the relocation of the village. The elements will be reconfigured to allow more natural light and ventilation, as well as to protect against future floods. A small prototype timber structure was built using existing knowledge and skills of local carpenters to test a part of the new design. The process throughout the planning, design and testing resembled the tradition of đôi công, the local form of mutual support. The importance of working through such traditions was reiterated when the project was interrupted by an unprecedented flash flood that destroyed a significant area of the village along with the assets of the cooperative. The process is expected to commence in autumn 2020.

Team: Alexander Eriksson Furunes, Hiep Nguyen, Chau Nguyen Huyen, Remi Gontier & Sudarshan Khadka Partner: Lung Tham Textile Cooperative

You’ve done admirable work with your community-driven design projects in Vietnam and the Philippines. In fact, your winning entry for the Philippine Pavilion for the Venice Biennale is a demonstration of this socially-immersive method of designing spaces. How does one encourage a community without a design background to participate in the design process?

People have an innate understanding of architecture since we all inhabit some form of dwelling. The impediments are the tools and the language we use to process and communicate our thoughts and ideas about architecture. Through our work, we try to simplify and clarify these tools so that communities engage in the design process through a mutual sharing of knowledge.

Ultimately, what do you want the community to learn or pick up about the experience?

That we all have the power to build. That we all have the power to determine the values and meanings embodied by our built environment.

Still on the subject of community, we can say that with this spatial crafting method, the skill, mindset, and process is just as much a vital heirloom as the space itself. With this in mind, do you see potential loss in that the community may decide not to get architects anymore? Or is this actually the desired effect? How can design forge stronger and more united communities?

Exactly! One natural outcome of our process is that we, as the architects, dissolve. It is a great feeling to know that the projects go on without us and that the systems to design and build on their own are in place.

In your community projects, how easy or hard is it to let go of something you’ve helmed design-wise? Are there steps you take to encourage the design integrity of a project that is now wholly in the hands of the community? Or do you allow the community free rein to make out how they want to use the space?

Knowledge is a form of power, and the goal of our process is to create a space for the mutual sharing of knowledge. We recognize that everyone has the experience, ideas, or expertise to contribute to the process. Creating this platform allows us to share and process architectural ideas with the community while they, too, share their experience and expertise with us. This shared understanding will enable decisions to be deliberated and determined as a group, so it never feels like we are letting go of something because it was always done together.

Streetlight Tagpuro: Tacloban, Philippines, 2016

Streetlight Tagpuro, Philippines is a WAF-winning, post-disaster reconstruction project, designed and built through the Filipino tradition of mutual support, bayanihan. In 2010, the community and architects built a study center for the children of the informal settlement Seawall in Tacloban City. When the city was devastated by super typhoon Haiyan in 2013, the building was destroyed by the storm surge. In the aftermath of the typhoon, the community came together through the same platform of bayanihan and invited the architects back to support their reconstruction efforts. Following the government order for relocation, the new site was moved to the inland area of Tagpuro. Building on the learnings from the 2010 project which closely engaged the children and the community of Seawall throughout the process of design and build, the project became centered around the importance of developing community ownership over the relocation and reconstruction. More than 100 workshops were organized to program, conceptualize and design the new buildings, and each workshop resembled the practice of bayanihan—strengthening social ties, capacity and resilience. Through drawings, models, and full-scale mockups, the community developed a common language to express and negotiate ideas and solutions that mattered to them as a group. The project completed in 2016 comprised of a study center building, an office/vocational training center and an orphanage.

Team: Alexander Eriksson Furunes & Leandro V. Locsin Partners (Sudarshan Khadka)

Partner: Streetlight Philippines

Let’s talk collaboration. We’ve seen different professional groups call out people who practice in their field without the required licenses and education. What’s your take on this, having collaborated with a wide range of trained and untrained talent? Should there be exceptions? Is it detrimental or beneficial for the architectural community to allow cross-pollination from other fields and practices?

I understand the protectionist instincts that pervade the discussions about collaboration within our professions locally. But the nature of the practice globally has shifted, and our laws need to expand to include more diverse ways of practicing. Buildings today require the input of so many professionals with overlapping expertise that it would be a disservice to limit ourselves only to those who hold a particular title.

Moreover, in our practice, we recognize that everyone has something to contribute to the design process. To exclude that potentially reduces the architecture’s potential to mean more things to more people.

Collaboration should be a good thing. But the infighting about licenses and diplomas gets in the way of meaningful dialogue within and among the design professions and non-professionals. What could professionals or their design orgs do to encourage equitable opportunities and exchange of skills without canceling people out?

Everyone should study more about the fields beyond their own. An expanded view of related fields allows a better appreciation of the expertise within each and the limitations of our own. Mutual respect and humility is a good starting point for these exchanges.

Let’s talk about beauty in architecture. Define beautiful architecture. Why should one pursue it? Would you say its pursuit is just as important as attaining peak spatial functionality?

The essence of architecture is not space, but the meaning ascribed to space. Beauty is our connection to meaning, the pursuit of which is a way by which we can dignify space. Beauty relates to the soul and other intangibles that make architecture complete. When we talk about beauty, it should not be interpreted to mean pretty objects, delightful composition, or soothing colors. Those are all part of an aesthetic experience, but it is superficial to dwell on this alone. The true expanse of beauty lies in depths and breadths beyond this. It seems frivolous to talk about beauty considering the social, political, and environmental issues that we face. But that is only because we do not see beauty as a fundamental human need. The need to connect to each other, to nature, to the larger universe. Those are all in the domain of meaning which is the object of aesthetics. It is easy to confuse semiotics and aesthetics as they both deal with meaning. But semiotics is about “how” and aesthetics is about “why.” Our pursuit of meaning through aesthetics is the difference between a human being and being human.

In your experience, how does one balance beauty and purpose within a space?

A lot of this balance is about the pursuit of clarity. It is the clarity of thought that leads to the resolution of both beauty and purpose.

Let’s go macro now. Would you say that the field of architecture, in general, needs to revisit its moral compass, especially with the specter of climate change hanging on the horizon?

In general, sharpening our moral compass is our responsibility first as good citizens of the world, and then our architectural responses follow from that. The profession itself is already quite aware of its role in climate change, so it is taking steps to be more responsible in terms of its intentions concerning sustainability and climate change. However, the complications arise during the translation of intentions into concrete actions because it is difficult to find the right balance between multiple variables of the same problem.

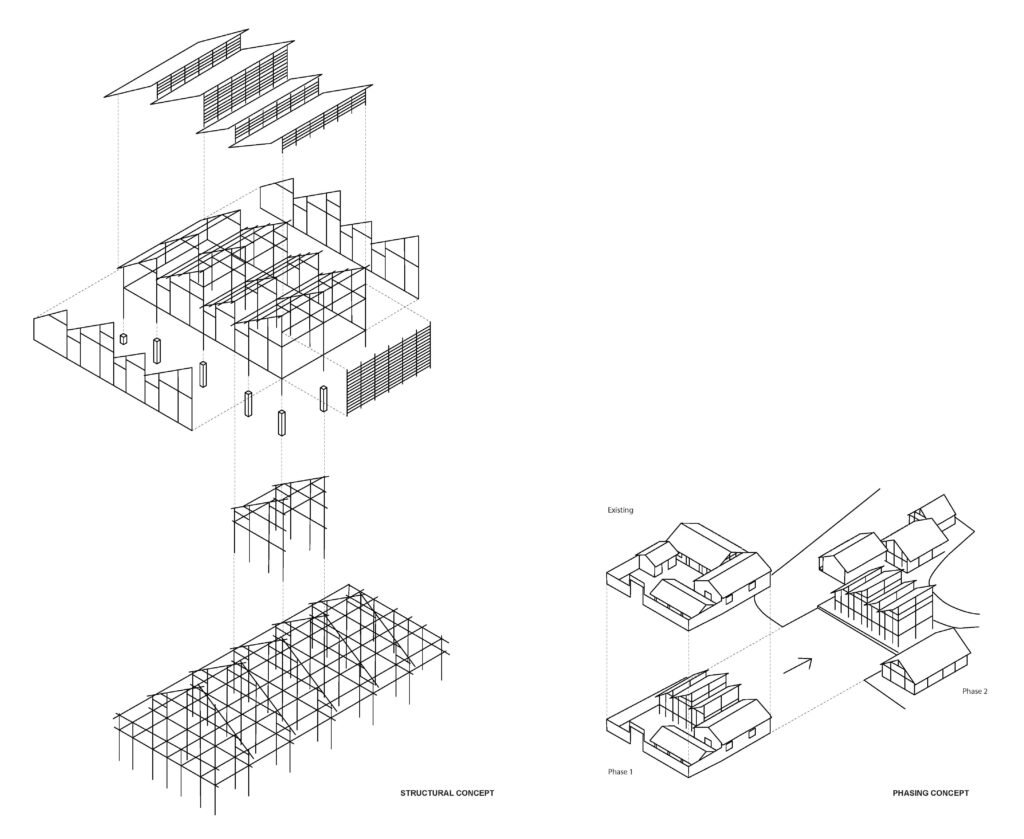

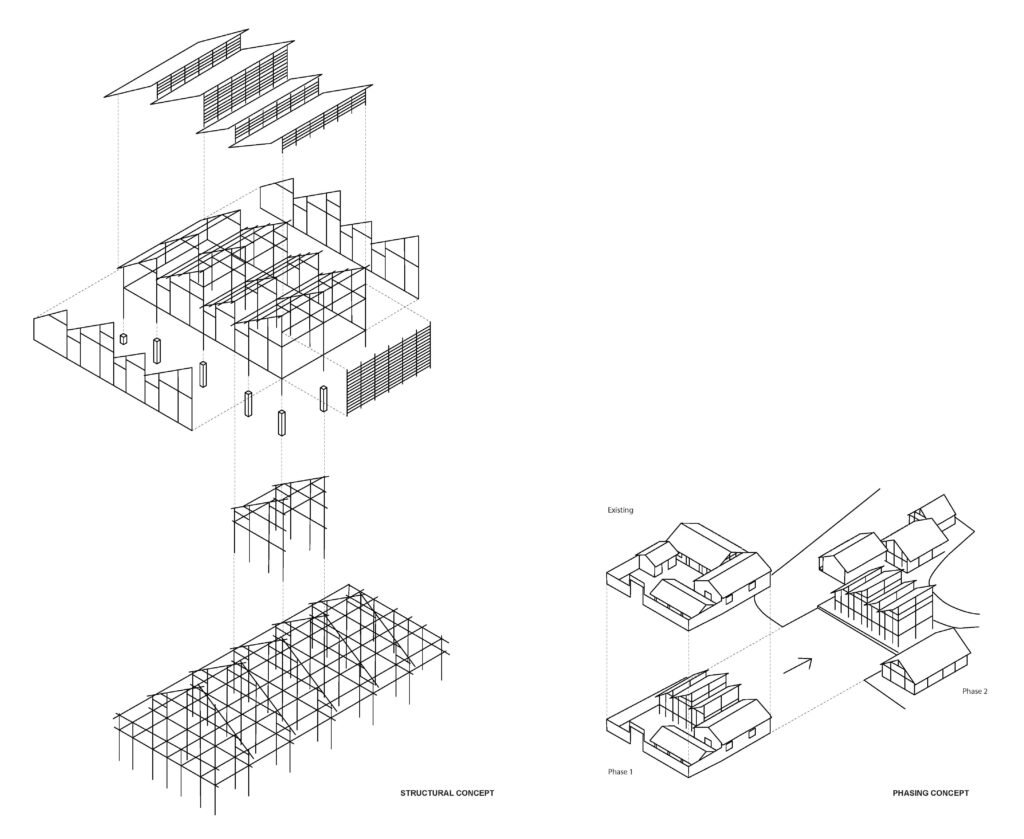

Structures of Mutual Support for the 2021 Venice Biennale

While bayanihan is unique to the Philippines, traditions of mutual support can be observed around the world, such as the Irish meitheal, the Norwegian dugnad, the Brasilian mutirão, or the Indonesian gotong-royong. These are traditions where communities come together to achieve a common goal. When applied in architectural praxis, the currency invested in projects by each community member is their time, knowledge, and skill rather than money. It is also about mutual sharing of power and agency. Based on these ideas, The Philippine Pavilion at the 17th Venice Architecture Biennale 2021 features a community library that doubles as a conflict resolution space. It was planned, designed, and built by the GK Enchanted Farm community together with the architects. In a world faced with increasing social and environmental challenges, it becomes increasingly important to ask the question “how will we live together?” as framed by the curatorial topic for the 2021 Venice Biennale. In response, our idea focuses on the way solutions are found, proposed, negotiated, and acted upon—rather than focusing on the answer itself. The question of how we live together is also a question of how we build together. Rather than seeing buildings as products to be bought and sold, we choose to approach architecture as a process. Utilizing mutual support as a platform, we can mobilize people on their own terms to reflect and take action on the processes that give shape to our built environment.

Team: Framework Collaborative: Alexander Eriksson Furunes & Sudarshan Khadka

Partner: Barangay Engkanto, PAVB-NCCA

In what fields or aspects of society do you think architecture should be more involved? Why so?

Architecture is both an aesthetic and political activity. How, why, and what we build are negotiations of competing intentions, interests, and values. As such, the resolution of these questions is necessarily about the politics of our aesthetics.

What makes you hopeful about being an architect in this less than ideal time?

In the Epic of Gilgamesh, he searches in vain for immortality, but in the end, he realizes that while we may all die, it is our civilization that will endure beyond us.

For this issue, we celebrate the invaluable lessons and inheritance the past has left us, but let us talk a little more about the future. What would you like your architectural legacy to be for the next generation?

We would like to think that the framework and process we are developing would endure beyond ourselves and would be a meaningful contribution to the way we build together.

What’s a project typology you’ve always wanted to design?

Khadka: Multi-family group housing and community libraries are typologies close to my heart. The first one is about how urban living can be made more suitable for those living in them. And the second one is about creating a social infrastructure for creative thought.

Sudar, you’re involved in a lot of community-driven architecture work with frequent partner Alexander Furunes. You’ve also worked at a prestigious firm and currently run your own practice. What insights about the field of architecture have you uncovered with your experiences of it in differing practices? How would you compare your reading of the field from when you began to where you are now?

I could share some insights I have learned not only about the field of architecture but more about the artistic journey we are all on:

Creativity is a fire that burns deep within us. It needs fuel to keep burning. Seek out those who keep their own fires burning and share them whenever you can.

Learn to understand what you hate; challenge yourself to understand it. There are human truths to be found underneath any ideology if there is enough empathy.

There are many ways to practice, and there are no rules about how things should be done. Do not be afraid to make your own. If you cannot find identity, define it. •

Architecture in progress over at @sudarkhadka and @alexerikssonfurunes on Instagram

5 Responses